Burkina Faso is a small, landlocked country north of Ghana and south of Mali and Niger.

Burkina Faso “Land of the honest men.” is a small land-locked country in West Africa bordered by Ghana and Togo to the south, Benin to the southeast, Niger to the east, Mali to the north and Ivory Coast to the southwest. Many of the ancient artistic traditions for which Africa is so well known have been preserved in Burkina Faso because so many people continue to honor the ancestral spirits, and the spirits of nature. In great part they honor the spirits through the use of masks and carved figures.

One of the principal obstacles to understanding the art of Burkina Faso, including that of the Bwa, has been a confusion between the styles of the Bwa, “gurunsi”, and Mossi, and a confusion of the Bwa people with their neighbors to the west the Bobo people. This confusion was the result of the use by French colonial officers of Jula interpreters at the turn of the century. These interpreters considered the two peoples to be the same and so referred to the Bobo as “Bobo-Fing” and to the Bwa as “Bobo-Oule.” In fact, these two peoples are not related at all. Their languages are quite different, their social systems are quite different, and certainly their art is quite different. In terms of artistic styles the confusion stems from the fact that the Bwa, “gurunsi'” and Mossi make masks that are covered with red white and black geometric graphic patterns. This is simply the style of the Voltaic or Gur peoples, and also includes the Dogon and other peoples who speak Voltaic languages.[3] (Wikipedia)

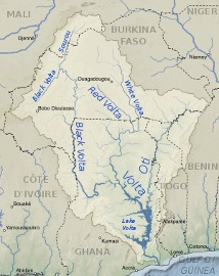

There are three main rivers in Burkina Faso: the Black, White and Red Voltas, which flow into Ghana. The country was previously called “Upper Volta” after the rivers.

Capital of Burkina Faso is Ouagadougou. Written as “Wogodogo” in the Mòoré dialect, it literally means “You are welcome here at home with us”.

Art

The African art sculptures of the Bobo, Bwa, Kurumba and Mossi people living in Burkina Faso frequently use and combine stylised elements borrowed from humans, animals or insects. It is the spirits of nature that are supposed to determine the well-being and prosperity of the individual and the community, and adversity is considered to be the result of neglect of collective rites. It is during celebrations that the mask can personify a nature spirit or an ancestor in order to influence the daily life of the members of the community. They will be used to honour the deceased during funeral rites, and to escort the souls to the kingdom of the dead. They are also used during agricultural festivals in order to mark the progression of the seasons, and during initiation rites to initiate young people into the responsibilities of adult life.

Tribes/tribus/Stämme

Mossi

The Mossi are the largest and most powerful culture in Burkina Faso and have a rich heritage of creating masks. Identification of Mossi masks can be a challenge, as they mix freely cross borders with other groups, like the Bwa, Bobo and Nuna, where we find similar art.

Like their relatives, the Bobo, the Mossi are mainly farmers.

The Mossis live in very arid savannas and have developed an elaborate rituals to invite sufficient rainfall.

Masked dances have the essential function of mediating evil, and reinstating a balance between sun, earth, and rain. At the end of the dry season, prior to the harvest, purification ceremonies take place, using impressive masks of fiber and wood, carved into forms representing the totemic spirits of the village: warthog, male buffalo, rooster, hornbill, fish, antelope, serpent, and hawk.

Together they incarnate the forces of fertility, abundance, and growth.

Among the Mossi, the sacredness of the mask derives from the fact that magic forces are considered to be present in the mask, and through it, to be acting on the behalf of the villagers.

Masks attend to honor the deceased and to verify that the spirit of the deceased merits admission into the world of ancestors. Without a proper funeral the spirit remains near the home and causes trouble for his/her descendants.

They are carved in three major styles that correspond to the styles of the ancient people who were conquered in 1500 by the invading Nakomse and integrated into a new Mossi society: In the north masks are vertical planks with a round concave or convex face.

In the southwest masks represent animals such as antelope, bush buffalo, and various strange creatures, are painted red, white and black. In the east, around Boulsa [3], masks have tall posts above the face to which fiber is attached, . Female masks have two pairs of round mirrors for eyes, and small masks, representing Yali, “the child” have two vertical horns. All Nyonyose masks are worn with thick costumes made of the fiber of the wild hemp,

Masks are very sacred, and are a link to the spirits of ancestors and of nature.

The Mossi make both political art and spiritual art. Figures are used by the ruling class to validate political power, and masks are used by the conquered peoples to control the forces of nature. Each year at the annual celebrations of the royal ancestors, figures of the deceased kings are displayed. On many occasions each year, especially during the long dry season from October to May, masks appear to honor the spirits of nature that control the forces of the environment. The several mask styles reflect the diversity of the population before the 15th century invasion. Long tall masks in the north are made by the descendants of the conquered Dogon population, while red, white, and black animal masks in the southwest are made by descendants of the conquered Gurunsi peoples.

Mossi dolls

POUPEES MOSSI BIGA FERTILITE, BURKINA FASO,

BOIS, ACQUIS DEBUT 1960, ÉPOQUE: DEBUT XXEME SIECLE

MOSSI BIGA FERTILITY DOLLS, BURKINA FASO,

WOOD, ACQUIRED EARLY 1960, PERIOD: EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Anthropomorphic figures, head can be very narrow with large crest, often long neck and stylized breasts, belly can indicate pregnancy, the hips extend outwards like a cone, no arms or legs, dolls are used as toys or as fertility symbols.

Mossi flutes

FLUTE EN BOIS – MOSSI – BURKINA FASO – AEROPHONES ACQUIS DÉBUT 1960, ÉPOQUE: DÉBUT XXÉME SIÈCLE

WOODEN FLUTE – MOSSI – BURKINA FASO – AEROPHONES ACQUIRED EARLY 1960, PERIOD: EARLY 20TH CENTURY

Longiform in structure like stylized human body,sometimes phallic at extremeties, oftern used as musical instrument when the masks come out into ceremony.

Kurumba

MASQUE CIMIER ADONE – KURUMBA MOSSI – BURKINA FASO, CIMIER DE DANSE REPRESENTANT UNE ANTILOPE, APPELE ADONE PAR LES KURUMBA (ASSIMILES AUX MOSSI), BOIS, POLYCHROME, ACQUIS FIN ANNEES 1960, ÉPOQUE FIN XX SIECLE.

Longiform in structure like stylized human body,sometimes phallic at extremeties, oftern used as musical instrument when the masks come out into ceremony.

Bwa

The Bwa people are very similar to other peoples in Burkina Faso in their lack of centralized political authority. Traditionally they have no chiefs. In contrast the Mossi people who live just to the east, have a strong system of chiefs and kings. the result is that while the Mossi are conservative and resistant to change, the Bwa are open-minded and receptive to change.

The Bwa produce several different kinds of masks, including leaf masks dedicated to the god named Dwo, and wooden masks dedicated to the god Lanle.

The style of the Bwa is well-known to collectors and scholars around the world. These are wooden masks that represent animals, or tall broad plank masks that represent the spirit Lanle. They are covered with red white and black graphic patterns that represent the religious laws that people in the villages must obey if they are to receive God’s blessings. These well-known patterns are not decorative, they are graphic patterns in a system of writing that can be read by anyone in the community who has been initiated. They include black-and-white checkerboards, that look like a target, zig-zag patterns that represent the path of the ancestors, X patterns, and crescents.[2]

Masks are used in a variety of different contexts. They appear at funerals of senior elders both male and female. They appear at initiation’s when young men and women are taught the meanings of the masks and the importance of the spirits and enter adult village society.

They are best known for their impressive plank masks which are used in the southern villages. Wooden sculptures used in fertility and divination ceremonies are also carved.

Bwa masks

MASQUE FAUCON PAPILLON BWA (DUHO), BURKINA FASO, MASQUE EN BOIS DE PLANCHE, FIBRES, TEXTILE INCORPORÉ POUR LE PORTEUR; FIN ANNÉES 1950, REGION DE LA RIVIERE VOLTA NOIRE ; BOIS, PIGMENT, FIBRE

MASQUE SERPENT, PEUPLES BWA, BURKINA FASO, OFFERT A LA FIN DES ANNEES 1960, BOIS, PIGMENT, BITUME, CHEVEUX, FIBRE VEGETALE

SERPENT MASK, BWA PEOPLES, BURKINA FASO, GIFTED IN LATE 1960S, WOOD, PIGMENT, BITUMEN, HAIR, PLANT FIBER

Bwa legend has it that the world was abandoned by God (Difini or Dobweni) after he was injured by a woman. To enable continued communication between man and himself, God sent his son, Do to earth to act as an intermediary. Through Do, humanity was given a lifeline as it is believed that Do represents the forest’s life-giving qualities (nature spirits). To harness the life-renewing forces of Do nature spirits, the head of a southern Bwa family commissions the creation of a large number and variety of wooden sculptures and masks to personify specific nature spirits (represented as humans, animals and other abstract beings). One such mask created is the doho, used to represent the serpent and believed to demonstrate the positivity and protective qualities of snakes in Bwa myths. Used during harvest celebrations, funeral rites and initiation ceremonies, doho masks are performed by masqueraders who mimic the movements and behaviours of the snake by twisting their heads rapidly from side to side. Describing the origin of the doho mask, Christopher Roy states that “many years ago the men of Dossi raided a neighboring village and were routed. An elder from Dossi hid from his vengeful pursuers in the burrow of a great serpent, saying to the serpent that he was not there to harm it but to save his own life. He was forced to hide for two market weeks, during which time the serpent brought game to the burrow for the elder to eat. When, eventually, the elder returned to Dossi, he consulted a diviner, who told him to carve a mask and to respect the serpent as a protective spirit.”2 For more on Bwa culture, see the article on The Art of Burkina Faso on the Art & Life in Africa website, hosted by the University of Iowa Museum of Art (UIMA)